Origin of birds

.jpg)

The origin of birds is a contentious and central topic within evolutionary biology. A close relationship between birds and dinosaurs was first proposed in the nineteenth century after the discovery of the primitive bird Archaeopteryx in Germany. To date, most researchers support the view that birds are a group of theropod dinosaurs that evolved during the Mesozoic Era.

Birds share a myriad of unique skeletal features with dinosaurs.[1] Moreover, fossils of more than twenty species of dinosaur have been collected which preserve feathers. There are even very small dinosaurs, such as Microraptor and Anchiornis, which have long, vaned, arm and leg feathers forming wings. The Jurassic basal avialan Pedopenna also shows these long foot feathers. Witmer (2009) has concluded that this evidence is sufficient to demonstrate that avian evolution went through a four-winged stage.[2]

Fossil evidence also demonstrates that birds and dinosaurs shared features such as hollow, pneumatized bones, gastroliths in the digestive system, nest-building and brooding behaviors. The ground-breaking discovery of fossilized Tyrannosaurus rex soft tissue allowed a molecular comparison of cellular anatomy and protein sequencing of collagen tissue, both of which demonstrated that T. rex and birds are more closely related than either is to Alligator.[3] A second molecular study robustly supported the relationship of birds to dinosaurs, though it did not place birds within Theropoda, as expected. This study utilized eight additional collagen sequences extracted from a femur of Brachylophosaurus canadensis, a hadrosaur.[4]

Only a few scientists still debate the dinosaurian origin of birds, suggesting descent from other types of archosaurian reptiles. Among the consensus that supports dinosaurian ancestry, the exact sequence of evolutionary events that gave rise to the early birds within maniraptoran theropods is a hot topic. The origin of bird flight is a separate but related question for which there are also several proposed answers.

Contents |

Research history

Huxley, Archaeopteryx and early research

.jpg)

Scientific investigation into the origin of birds began shortly after the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, the ground-breaking book which described his theory of evolution by natural selection.[5] In 1860, a fossilized feather was discovered in Germany's Late Jurassic solnhofen limestone. Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer described this feather as Archaeopteryx lithographica the next year,[6] and Richard Owen described a nearly complete skeleton in 1863, recognizing it as a bird despite many features reminiscent of reptiles, including clawed forelimbs and a long, bony tail.[7]

Biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his ferocious support of the new theory of evolution, almost immediately seized upon Archaeopteryx as a transitional fossil between birds and reptiles. Starting in 1868, Huxley made detailed comparisons of Archaeopteryx with various prehistoric reptiles and found that it was most similar to dinosaurs like Hypsilophodon and Compsognathus.[8][9] The discovery in the late 1870s of the iconic "Berlin specimen" of Archaeopteryx, complete with a set of reptilian teeth, provided further evidence. Huxley was the first to propose an evolutionary relationship between birds and dinosaurs, although he was opposed by the very influential Owen, who remained a staunch creationist. Huxley's conclusions were accepted by many biologists, including Baron Franz Nopcsa,[10] while others, notably Harry Seeley,[11] argued that the similarities were due to convergent evolution.

Heilmann and the thecodont hypothesis

A turning point came in the early twentieth century with the writings of Gerhard Heilmann of Denmark. An artist by trade, Heilmann had a scholarly interest in birds and from 1913 to 1916 published the results of his research in several parts, dealing with the anatomy, embryology, behavior, paleontology, and evolution of birds.[12] His work, originally written in Danish as Vor Nuvaerende Viden om Fuglenes Afstamning, was compiled, translated into English, and published in 1926 as The Origin of Birds.

Like Huxley, Heilmann compared Archaeopteryx and other birds to an exhaustive list of prehistoric reptiles, and also came to the conclusion that theropod dinosaurs like Compsognathus were the most similar. However, Heilmann noted that birds possessed clavicles (collar bones) fused to form a bone called the furcula ("wishbone"), and while clavicles were known in more primitive reptiles, they had not yet been recognized in dinosaurs. Since he was a firm believer in Dollo's law, which states that evolution is not reversible, Heilmann could not accept that clavicles were lost in dinosaurs and re-evolved in birds. He was therefore forced to rule out dinosaurs as bird ancestors and ascribe all of their similarities to convergent evolution. Heilmann stated that bird ancestors would instead be found among the more primitive "thecodont" grade of reptiles.[13] Heilmann's extremely thorough approach ensured that his book became a classic in the field, and its conclusions on bird origins, as with most other topics, were accepted by nearly all evolutionary biologists for the next four decades.[14]

Clavicles are relatively delicate bones and therefore in danger of being destroyed or at least damaged beyond recognition. Nevertheless clavicles had been found in theropod dinosaurs before Heilman wrote his book, but had gone unrecognized.[15] The absence of clavicles in dinosaurs became the orthodox view despite the discovery of clavicles in the primitive theropod Segisaurus in 1936.[16] The next report of clavicles in a dinosaur was in 1983, and that was in a Russian article published before the end of the Cold War.[17]

Contrary to what Heilman believed, paleontologists now accept that clavicles and in most cases furculae are a standard feature not just of theropods but of saurischian dinosaurs. Up to late 2007 ossified furculae (i.e. made of bone rather than cartilage) have been found in nearly all types of theropods except the most basal ones, Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus.[18] The original report of a furcula in the primitive theropod Segisaurus (1936) has been confirmed by a re-examination in 2005.[19] Joined, furcula-like clavicles have also been found in Massospondylus, an Early Jurassic sauropodomorph.[20]

Ostrom, Deinonychus and the Dinosaur Renaissance

The tide began to turn against the 'thecodont' hypothesis after the 1964 discovery of a new theropod dinosaur in Montana. In 1969, this dinosaur was described and named Deinonychus by John Ostrom of Yale University.[21] The next year, Ostrom redescribed a specimen of Pterodactylus in the Dutch Teyler Museum as another skeleton of Archaeopteryx.[22] The specimen consisted mainly of a single wing and its description made Ostrom aware of the similarities between the wrists of Archaeopteryx and Deinonychus.[23]

In 1972, British paleontologist Alick Walker hypothesized that birds arose not from 'thecodonts' but from crocodile ancestors like Sphenosuchus.[24] Ostrom's work with both theropods and early birds led him to respond with a series of publications in the mid-1970s in which he laid out the many similarities between birds and theropod dinosaurs, resurrecting the ideas first put forth by Huxley over a century before.[25][26][27] Ostrom's recognition of the dinosaurian ancestry of birds, along with other new ideas about dinosaur metabolism,[28] activity levels, and parental care,[29] began what is known as the Dinosaur renaissance, which began in the 1970s and continues to this day.

Ostrom's revelations also coincided with the increasing adoption of phylogenetic systematics (cladistics), which began in the 1960s with the work of Willi Hennig.[30] Cladistics is a method of arranging species based strictly on their evolutionary relationships, using a statistical analysis of their anatomical characteristics. In the 1980s, cladistic methodology was applied to dinosaur phylogeny for the first time by Jacques Gauthier and others, showing unequivocally that birds were a derived group of theropod dinosaurs.[31] Early analyses suggested that dromaeosaurid theropods like Deinonychus were particularly closely related to birds, a result which has been corroborated many times since.[32][33]

Modern research and feathered dinosaurs in China

The early 1990s saw the discovery of spectacularly preserved bird fossils in several Early Cretaceous geological formations in the northeastern Chinese province of Liaoning.[34][35] In 1996, Chinese paleontologists described Sinosauropteryx as a new genus of bird from the Yixian Formation,[36] but this animal was quickly recognized as a theropod dinosaur closely related to Compsognathus. Surprisingly, its body was covered by long filamentous structures. These were dubbed 'protofeathers' and considered to be homologous with the more advanced feathers of birds,[37] although some scientists disagree with this assessment.[38] Chinese and North American scientists described Caudipteryx and Protarchaeopteryx soon after. Based on skeletal features, these animals were non-avian dinosaurs, but their remains bore fully-formed feathers closely resembling those of birds.[39] "Archaeoraptor," described without peer review in a 1999 issue of National Geographic,[40] turned out to be a smuggled forgery,[41] but legitimate remains continue to pour out of the Yixian, both legally and illegally. Feathers or "protofeathers" have been found on a wide variety of theropods in the Yixian,[42][43] and the discoveries of extremely bird-like dinosaurs,[44] as well as dinosaur-like primitive birds,[45] have almost entirely closed the morphological gap between theropods and birds.

A small minority, including ornithologists Alan Feduccia and Larry Martin, continues to assert that birds are instead the descendants of earlier archosaurs, such as Longisquama or Euparkeria.[46][47] Embryological studies of bird developmental biology have raised questions about digit homology in bird and dinosaur forelimbs.[48] However, due to the cogent evidence provided by comparative anatomy and phylogenetics, as well as the dramatic feathered dinosaur fossils from China, the idea that birds are derived dinosaurs, first championed by Huxley and later by Nopcsa and Ostrom, enjoys near-unanimous support among today's paleontologists.[14]

Phylogeny

Archaeopteryx has historically been considered the first bird, or Urvogel. Although newer fossil discoveries eliminated the gap between theropods and Archaeopteryx, as well as the gap between Archaeopteryx and modern birds, phylogenetic taxonomists, in keeping with tradition, almost always use Archaeopteryx as a specifier to help define Aves.[49][50] Aves has more rarely been defined as a crown group consisting only of modern birds.[31] Nearly all palaeontologists regard birds as coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs.[14] Within Coelurosauria, multiple cladistic analyses have found support for a clade named Maniraptora, consisting of therizinosauroids, oviraptorosaurs, troodontids, dromaeosaurids, and birds.[32][33][51] Of these, dromaeosaurids and troodontids are usually united in the clade Deinonychosauria, which is a sister group to birds (together forming the node-clade Eumaniraptora) within the stem-clade Paraves.[32][52]

Other studies have proposed alternative phylogenies in which certain groups of dinosaurs that are usually considered non-avian are suggested to have evolved from avian ancestors. For example, a 2002 analysis found oviraptorosaurs to be basal avians.[53] Alvarezsaurids, known from Asia and the Americas, have been variously classified as basal maniraptorans,[32][33][54][55] paravians,[51] the sister taxon of ornithomimosaurs,[56] as well as specialized early birds.[57][58] The genus Rahonavis, originally described as an early bird,[59] has been identified as a non-avian dromaeosaurid in several studies.[52][60] Dromaeosaurids and troodontids themselves have also been suggested to lie within Aves rather than just outside it.[61][62]

Features linking birds and dinosaurs

Many distinct anatomical[63] features are shared by birds and theropod dinosaurs. Some of the more interesting similarities are discussed here:

Feathers

- Blank out numbers in image

(calamus)

Archaeopteryx, the first good example of a "feathered dinosaur", was discovered in 1861. The initial specimen was found in the solnhofen limestone in southern Germany, which is a lagerstätte, a rare and remarkable geological formation known for its superbly detailed fossils. Archaeopteryx is a transitional fossil, with features clearly intermediate between those of modern reptiles and birds. Discovered just two years after Darwin's seminal Origin of Species, its discovery spurred the nascent debate between proponents of evolutionary biology and creationism. This early bird is so dinosaur-like that, without a clear impression of feathers in the surrounding rock, at least one specimen was mistaken for Compsognathus.[64]

Since the 1990s, a number of additional feathered dinosaurs have been found, providing even stronger evidence of the close relationship between dinosaurs and modern birds. Most of these specimens were unearthed in Liaoning province, northeastern China, which was part of an island continent during the Cretaceous period. Though feathers have been found only in the lagerstätte of the Yixian Formation and a few other places, it is possible that non-avian dinosaurs elsewhere in the world were also feathered. The lack of widespread fossil evidence for feathered non-avian dinosaurs may be due to the fact that delicate features like skin and feathers are not often preserved by fossilization and thus are absent from the fossil record.

A recent development in the debate centers around the discovery of impressions of "protofeathers" surrounding many dinosaur fossils. These protofeathers suggest that the tyrannosauroids may have been feathered.[65] However, others claim that these protofeathers are simply the result of the decomposition of collagenous fiber that underlaid the dinosaurs' integument.[47]

The feathered dinosaurs discovered so far include Beipiaosaurus, Caudipteryx, Dilong, Microraptor, Protarchaeopteryx, Shuvuuia, Sinornithosaurus, Sinosauropteryx, and Jinfengopteryx, along with dinosaur-like birds, such as Confuciusornis, which are anatomically closer to modern avians. All of them have been found in the same area and formation, in northern China. The Dromaeosauridae family, in particular, seems to have been heavily feathered and at least one dromaeosaurid, Cryptovolans, may have been capable of flight.

Skeleton

Because feathers are often associated with birds, feathered dinosaurs are often touted as the missing link between birds and dinosaurs. However, the multiple skeletal features also shared by the two groups represent the more important link for paleontologists. Furthermore, it is increasingly clear that the relationship between birds and dinosaurs, and the evolution of flight, are more complex topics than previously realized. For example, while it was once believed that birds evolved from dinosaurs in one linear progression, some scientists, most notably Gregory S. Paul, conclude that dinosaurs such as the dromaeosaurs may have evolved from birds, losing the power of flight while keeping their feathers in a manner similar to the modern ostrich and other ratites.

Comparisons of bird and dinosaur skeletons, as well as cladistic analysis, strengthens the case for the link, particularly for a branch of theropods called maniraptors. Skeletal similarities include the neck, pubis, wrist (semi-lunate carpal), arm and pectoral girdle, shoulder blade, clavicle, and breast bone.

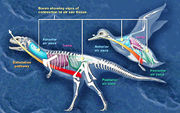

Lungs

Large meat-eating dinosaurs had a complex system of air sacs similar to those found in modern birds, according to an investigation which was led by Patrick M. O'Connor of Ohio University. The lungs of theropod dinosaurs (carnivores that walked on two legs and had birdlike feet) likely pumped air into hollow sacs in their skeletons, as is the case in birds. "What was once formally considered unique to birds was present in some form in the ancestors of birds", O'Connor said. The study was funded in part by the National Science Foundation.[66][67]

Heart and sleeping posture

Modern computed tomography (CT) scans of a dinosaur chest cavity (conducted in 2000) found the apparent remnants of complex four-chambered hearts, much like those found in today's mammals and birds.[68] The idea is controversial within the scientific community, coming under fire for bad anatomical science[69] or simply wishful thinking.[70] A recently discovered troodont fossil demonstrates that the dinosaurs slept like certain modern birds, with their heads tucked under their arms.[71] This behavior, which may have helped to keep the head warm, is also characteristic of modern birds.

Reproductive biology

When laying eggs, female birds grow a special type of bone in their limbs. This medullary bone, which is rich in calcium, forms a layer inside the hard outer bone that is used to make eggshells. The presence of endosteally-derived bone tissues lining the interior marrow cavities of portions of a Tyrannosaurus rex specimen's hind limb suggested that T. rex used similar reproductive strategies, and revealed the specimen to be female.[72] Further research has found medullary bone in the theropod Allosaurus and ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Because the line of dinosaurs that includes Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus diverged from the line that led to Tenontosaurus very early in the evolution of dinosaurs, this suggests that dinosaurs in general produced medullary tissue.[73]

Brooding and care of young

Several Citipati specimens have been found resting over the eggs in its nest in a position most reminiscent of brooding.[74]

Numerous dinosaur species, for example Maiasaura, have been found in herds mixing both very young and adult individuals, suggesting rich interactions between them.

A dinosaur embryo was found without teeth, which suggests some parental care was required to feed the young dinosaur, possibly the adult dinosaur regurgitated food into the young dinosaur's mouth (see altricial). This behaviour is seen in numerous bird species; parent birds regurgitate food into the hatchling's mouth.

Gizzard stones

Both birds and dinosaurs use gizzard stones. These stones are swallowed by animals to aid digestion and break down food and hard fibres once they enter the stomach. When found in association with fossils, gizzard stones are called gastroliths.[75] Gizzard stones are also found in some fish (mullets, mud shad, and the gilaroo, a type of trout) and in crocodiles.

Molecular evidence and soft tissue

One of the best examples of soft tissue impressions in a fossil dinosaur was discovered in Petraroia, Italy. The discovery was reported in 1998, and described the specimen of a small, very young coelurosaur, Scipionyx samniticus. The fossil includes portions of the intestines, colon, liver, muscles, and windpipe of this immature dinosaur.[76]

In the March 2005 issue of Science, Dr. Mary Higby Schweitzer and her team announced the discovery of flexible material resembling actual soft tissue inside a 68-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex leg bone from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana. After recovery, the tissue was rehydrated by the science team. The seven collagen types obtained from the bone fragments, compared to collagen data from living birds (specifically, a chicken), suggest that older theropods and birds are closely related.

When the fossilized bone was treated over several weeks to remove mineral content from the fossilized bone marrow cavity (a process called demineralization), Schweitzer found evidence of intact structures such as blood vessels, bone matrix, and connective tissue (bone fibers). Scrutiny under the microscope further revealed that the putative dinosaur soft tissue had retained fine structures (microstructures) even at the cellular level. The exact nature and composition of this material, and the implications of Dr. Schweitzer's discovery, are not yet clear; study and interpretation of the specimens is ongoing.[77]

The successful extraction of ancient DNA from dinosaur fossils has been reported on two separate occasions, but upon further inspection and peer review, neither of these reports could be confirmed.[78] However, a functional visual peptide of a theoretical dinosaur has been inferred using analytical phylogenetic reconstruction methods on gene sequences of related modern species such as reptiles and birds.[79] In addition, several proteins have putatively been detected in dinosaur fossils,[80] including hemoglobin.[81]

Debates

Origin of bird flight

Debates about the origin of bird flight are almost as old as the idea that birds evolved from dinosaurs, which arose soon after the discovery of Archaeopteryx in 1862. Two theories have dominated most of the discussion since then: the cursorial ("from the ground up") theory proposes that birds evolved from small, fast predators that ran on the ground; the arboreal ("from the trees down") theory proposes that powered flight evolved from unpowered gliding by arboreal (tree-climbing) animals. A more recent theory, "wing-assisted incline running" (WAIR), is a variant of the cursorial theory and proposes that wings developed their aerodynamic functions as a result of the need to run quickly up very steep slopes, for example to escape from predators.

Cursorial ("from the ground up") theory

The cursorial theory of the origin of flight was first proposed by Samuel Wendell Williston, and elaborated upon by Baron Nopcsa. This hypothesis proposes that some fast-running animals with long tails used their arms to keep their balance while running. Modern versions of this theory differ in many details from the Williston-Nopcsa version, mainly as a result of discoveries since Nopcsa's time.

Nopcsa theorized that increasing the surface area of the outstretched arms could have helped small cursorial predators to keep their balance, and that the scales of the forearms became elongated, evolving into feathers. The feathers could also have been used as a trap to catch insects or other prey. Progressively, the animals would have leapt for longer distances, helped by their evolving wings. Nopcsa also proposed that there were three main stages in the evolution of flight. First, passive flight was realized, in which the developed wing structures served as a sort of parachute. Second, active flight was possible, in which the animal achieved flight by flapping its wings. He used Archaeopteryx as an example of this second stage. Finally, birds gained the ability to soar.[82]

It is now thought that feathers did not evolve from scales, as feathers are made of different proteins.[83] More seriously, Nopcsa's theory assumes that feathers evolved as part of the evolution of flight, and recent discoveries prove that assumption is false.

Feathers are very common in coelurosaurian dinosaurs (including the early tyrannosauroid Dilong).[84] Modern birds are classified as coelurosaurs by nearly all palaeontologists,[85] though not by a few ornithologists.[86][87] The modern version of the "from the ground up" hypothesis argues that birds' ancestors were small, feathered, ground-running predatory dinosaurs (rather like roadrunners in their hunting style[88]) that used their forelimbs for balance while pursuing prey, and that the forelimbs and feathers later evolved in ways that provided gliding and then powered flight. The most widely-suggested original functions of feathers include thermal insulation and competitive displays, as in modern birds.[89][90]

All of the Archaeopteryx fossils come from marine sediments and it has been suggested that wings may have helped the birds run over water in the manner of the Jesus Christ Lizard (Common basilisk).[91]

Most recent refutations of the "from the ground up" hypothesis attempt to refute the modern version's assumption that birds are modified coelurosaurian dinosaurs. The strongest attacks are based on embryological analyses which conclude that birds' wings are formed from digits 2, 3, and 4 (corresponding to the index, middle, and ring fingers in humans; the first of a bird's three digits forms the alula, which they use to avoid stalling in low-speed flight, for example when landing); but the hands of coelurosaurs are formed by digits 1, 2, and 3 (thumb and first two fingers in humans).[92] However these embryological analyses were immediately challenged on the embryological grounds that the "hand" often develops differently in clades that have lost some digits in the course of their evolution, and that birds' "hands" do develop from digits 1, 2, and 3.[93][94][94] This debate is complex and not yet resolved - see "Digit homology" below.

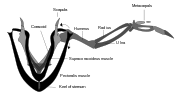

Wing-assisted incline running

The WAIR hypothesis was prompted by observation of young chukar chicks, and proposes that wings developed their aerodynamic functions as a result of the need to run quickly up very steep slopes such as tree trunks, for example to escape from predators.[95] This makes it a specialized type of cursorial ("from the ground up") theory. Note that in this scenario birds need downforce to give their feet increased grip.[96][97] But early birds, including Archaeopteryx, lacked the shoulder mechanism by which modern birds' wings produce swift, powerful upstrokes; since the downforce on which WAIR depends is generated by upstrokes, it seems that early birds were incapable of WAIR.[98]

Arboreal ("from the trees down") theory

.jpg)

Most versions of the arboreal hypothesis state that the ancestors of birds were very small dinosaurs that lived in trees, springing from branch to branch. This small dinosaur already had feathers, which were co-opted by evolution to produce longer, stiffer forms that were useful in aerodynamics, eventually producing wings. Wings would have then evolved and become increasingly refined as devices to give the leaper more control, to parachute, to glide, and to fly in stepwise fashion. The arboreal hypothesis also notes that, for arboreal animals, aerodynamics are far more energy efficient, since such animals simply fall in order to achieve minimum gliding speeds.[99][100]

Several small dinosaurs from the Jurassic or Early Cretaceous, all with feathers, have been interpreted as possibly having arboreal and/or aerodynamic adaptations. These include Epidendrosaurus, Epidexipteryx, Microraptor, Pedopenna, and Anchiornis. Anchiornis is particularly important to this subject, as it is the smallest known non - avian dinosaur, and it lived at the beginning of the Late Jurassic, long before Archaeopteryx.[101]

Analysis of the proportions of the toe bones of the most primitive birds Archaeopteryx and Confuciusornis, compared to those of living species, suggest that the early species may have lived both on the ground and in trees.[102]

One study suggested that the earliest birds and their immediate ancestors did not climb trees. This study determined that the amount of toe claw curvature of early birds was more like that seen in modern ground-foraging birds than in perching birds.[103]

The diminished significance of Archaeopteryx

Archaeopteryx was the first and for a long time the only known feathered Mesozoic animal (or dinosaur, if one accepts the majority view that birds are modified dinosaurs). As a result, discussion of the evolution of birds and of bird flight centered on Archaeopteryx at least until the mid-1990s.

There has been debate about whether Archaeopteryx could really fly. It appears that Archaeopteryx had the brain structures and inner-ear balance sensors that birds use to control their flight.[104] Archaeopteryx also had a wing feather arrangement like that of modern birds and similarly asymmetrical flight feathers on its wings and tail. But Archaeopteryx lacked the shoulder mechanism by which modern birds' wings produce swift, powerful upstrokes (see diagram above of supracoracoideus pulley); this may mean that it and other early birds were incapable of flapping flight and could only glide.[98]

But the discovery since the early 1990s of many feathered dinosaurs means that Archaeopteryx is no longer the key figure in the evolution of bird flight. Other small, feathered coelurosaurs from the Cretaceous and Late Jurassic show features that may be precursors of avian flight, for example: Rahonavis, a ground-runner which had a Velociraptor-like raised sickle claw on the second toe and which some paleontologists think was better adapted for flight than Archaeopteryx;[105] Epidendrosaurus, an arboreal dinosaur that may provide some support for the "from the trees down" theory;[106] Microraptor, an arboreal dinosaur that may have been capable of powered flight but, if so, more like a biplane, as it had well-developed feathers on its legs.[107] As early as 1915, some scientists had argued that the evolution of bird flight may have gone through a four-winged (or tetrapteryx) stage.[108][109]

Secondary flightlessness in dinosaurs

| Coelurosaurs |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Groups usually regarded as birds are in bold type.[62]

A hypothesis, credited to Gregory Paul and propounded in his books Predatory Dinosaurs of the World (1988) and Dinosaurs of the Air (2002), suggests that some groups of non-flying carnivorous dinosaurs, especially deinonychosaurs but perhaps others such as oviraptorosaurs, therizinosaurs, alvarezsaurids and ornithomimosaurs, are actually descended from birds. Paul also proposed that the bird ancestor of these groups was more advanced in its flight adaptations than Archaeopteryx. This would mean that Archaeopteryx is thus less closely related to extant birds than these dinosaurs are.[110]

Paul's hypothesis received additional support when Mayr et al. (2005) analyzed a new, tenth specimen of Archaeopteryx, and concluded that Archaeopteryx was the sister clade to the Deinonychosauria, but that the more advanced bird Confuciusornis was within the Dromaeosauridae. This result supports Paul's hypothesis, suggesting that the Deinonychosauria and the Troodontidae are part of Aves, the bird lineage proper, and secondarily flightless.[111] This paper, however, excluded all other birds and thus did not sample their character distributions. The paper was criticized by Corfe and Butler (2006) who found the authors could not support their conclusions statistically. Mayr et al. agreed that the statistical support was weak, but added that it is also weak for the alternative scenarios.[112]

Paul's hypothesis about the position of Archaeopteryx is not supported by current cladistic analyses which generally find that Archaeopteryx is closer to birds, within the clade Avialae, than it is to deinonychosaurs or oviraptorosaurs. However, the version of this theory stating that some non-flying carnivorous dinosaurs may have had flying ancestors is supported by some fossils. Especially, Microraptor, Pedopenna, and Anchiornis all have winged feet, share many features, and lie close to the base of the clade Paraves. This suggests that the ancestral paravian was a four-winged glider, and that larger Deinonychosaurs secondarily lost the ability to glide, while the bird lineage increased in aerodynamic ability as it progressed.[2]

Digit homology

There is a debate between embryologists and paleontologists whether the hands of theropod dinosaurs and birds are essentially different, based on phalangeal counts, a count of the number of phalanges (fingers) in the hand. This is an important and fiercely debated area of research because its results may challenge the consensus that birds are descendants of dinosaurs.

Embryologists and some paleontologists who oppose the bird-dinosaur link, have long numbered the digits of birds II-III-IV on the basis of multiple studies of the development in the egg.[113][114][115] [116][117] This is based on the fact that in most amniotes, the first digit to form in a 5-fingered hand is digit IV, which develops a primary axis. Therefore, embryologists have identified the primary axis in birds as digit IV, and the surviving digits as II-III-IV. The fossils of advanced theropod (Tetanurae) hands appear to have the digits I-II-III (some genera within Avetheropoda also have a reduced digit IV[118]). If this is true, then the II-III-IV development of digits in birds is an indication against theropod (dinosaur) ancestry. However, with no ontogenical (developmental) basis to definitively state which digits are which on a theropod hand (because no non-avian theropods can be observed growing and developing today), the labelling of the theropod hand is not absolutely conclusive.

Paleontologists have traditionally identified avian digits as I-II-III. They argue that the digits of birds number I-II-III, just as those of theropod dinosaurs do, by the conserved phalangeal formula. The phalangeal count for archosaurs is 2-3-4-5-3; many archosaur lineages have a reduced number of digits, but have the same phalangeal formula in the digits that remain. In other words, paleontologists assert that archosaurs of different lineages tend to lose the same digits when digit loss occurs, from the outside to the inside. The three digits of dromaeosaurs, and Archaeopteryx have the same phalangeal formula of I-II-III as digits I-II-III of basal archosaurs. Therefore, the lost digits would be V and IV. If this is true, then modern birds would also possess digits I-II-III.[117] Also, one research team has proposed a frame-shift in the digits of the theropod line leading to birds (thus making digit I into digit II, II to III, and so forth).[119][120] However, such frame shifts are rare in amniotes and would have had to occur solely in the forelimbs and not the hindlimbs (a condition presently unknown in any animal) in the bird-theropod lineage in order to be consistent with the theropod origin of birds.[121] This is called Lateral Digit Reduction (LDR) versus Bilateral Digit Reduction (BDR) (see also Limusaurus[122])

See also

- Bird ichnology

- List of extinct birds

- Feathered dinosaurs

- Flightless birds

- Origin of avian flight

- Temporal paradox (paleontology)

Footnotes

- ↑ Chiappe, Luis M. (2009). "Downsized Dinosaurs: The Evolutionary Transition to Modern Birds". Evolution: Education and Outreach: 248–256. http://www.springerlink.com/content/66w3755838876571/. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Witmer, Lawrence M. (2009) "Feathered dinosaurs in a tangle"NATURE|Vol 461|1 October 2009 pg 601-602

- ↑ Asara, JM; Schweitzer MH, Freimark LM, Phillips M, Cantley LC (2007). "Protein Sequences from Mastodon and Tyrannosaurus Rex Revealed by Mass Spectrometry". Science 316 (5822): 280–285. doi:10.1126/science.1137614. PMID 17431180.

- ↑ Schweitzer, M. H.; Zheng W., Organ C. L., Avci R., Suo Z., Freimark L. M., Lebleu V. S., Duncan M. B., Vander Heiden M. G., Neveu J. M., Lane W. S., Cottrell J. S., Horner J. R., Cantley L. C., Kalluri R. & Asara J. M. (2009). "Biomolecular Characterization and Protein Sequences of the Campanian Hadrosaur B. canadensis". Science 324 (5927): 626–631. doi:10.1126/science.1165069. PMID 19407199.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles R. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London: John Murray. p. 502pp. ISBN 1435393864. http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F373&viewtype=side&pageseq=16.

- ↑ von Meyer, C.E. Hermann. (1861). "Archaeopteryx lithographica (Vogel-Feder) und Pterodactylus von Solnhofen" (in German). Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie 1861: 678–679.

- ↑ Owen, Richard. (1863). "On the Archeopteryx [sp] of von Meyer, with a description of the fossil remains of a long-tailed species, from the lithographic stone of Solenhofen [sp]". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 153: 33–47. doi:10.1098/rstl.1863.0003.

- ↑ Huxley, Thomas H. (1868). "On the animals which are most nearly intermediate between birds and reptiles". Annals of the Magazine of Natural History 4 (2): 66–75.

- ↑ Huxley, Thomas H. (1870). "Further evidence of the affinity between the dinosaurian reptiles and birds". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 26: 12–31. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1870.026.01-02.08.

- ↑ Nopcsa, Franz. (1907). "Ideas on the origin of flight". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 223–238.

- ↑ Seeley, Harry G. (1901). Dragons of the Air: An Account of Extinct Flying Reptiles. London: Methuen & Co.. p. 239pp.

- ↑ Nieuwland, Ilja J.J. (2004). "Gerhard Heilmann and the artist’s eye in science, 1912-1927". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 3 (2). http://www.palarch.nl/wp-content/ver_2004_3_2.pdf.

- ↑ Heilmann, Gerhard (1926). The Origin of Birds. London: Witherby. p. 208pp. ISBN 0486227847.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Padian, Kevin. (2004). "Basal Avialae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; & Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 210–231. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ For example in 1923, 3 years before Heilmans's book, Roy Chapman Andrews found a good Oviraptor fossil in Mongolia, but Henry Fairfield Osborn, who analyzed the fossil in 1924, mis-identified the furcula as an interclavicle; described in Paul, G.S. (2002). Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. JHU Press. ISBN 0801867630. http://books.google.com/?id=OUwXzD3iihAC&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=oviraptor+furcula.

- ↑ Camp, Charles L. (1936). "A new type of small theropod dinosaur from the Navajo Sandstone of Arizona". Bulletin of the University of California Department of Geological Sciences 24: 39–65.

- ↑ In an Oviraptor: Barsbold, R. (1983). "[Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia". Trudy Soumestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontogicheskaya Ekspeditsiya 19: 1–117. (in Russian!) See the summary an pictures at "A wish for Coelophysis". http://www.hmnh.org/archives/2007/10/11/a-wish-for-coelophysis/.

- ↑ Lipkin, C., Sereno, P.C., and Horner, J.R. (November 2007). "THE FURCULA IN SUCHOMIMUS TENERENSIS AND TYRANNOSAURUS REX (DINOSAURIA: THEROPODA: TETANURAE)". Journal of Paleontology 81 (6): 1523–1527. doi:10.1666/06-024.1. http://jpaleontol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/extract/81/6/1523. - full text currently online at "The Furcula in Suchomimus Tenerensis and Tyrannosaurus rex". http://www.redorbit.com/news/health/1139122/the_furcula_in_suchomimus_tenerensis_and_tyrannosaurus_rex_dinosauria_theropoda/index.html. This lists a large number of theropods in which furculae have been found, as well as describing those of Suchomimus Tenerensis and Tyrannosaurus rex.

- ↑ Carrano, M,R., Hutchinson, J.R., and Sampson, S.D. (December 2005). "New information on Segisaurus halli, a small theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Arizona". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (4): 835–849. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0835:NIOSHA]2.0.CO;2. http://www.rvc.ac.uk/AboutUs/Staff/jhutchinson/documents/JH18.pdf.

- ↑ Yates, Adam M.; and Vasconcelos, Cecilio C. (2005). "Furcula-like clavicles in the prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (2): 466–468. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0466:FCITPD]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Ostrom, John H. (1969). "Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an unusual theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 30: 1–165.

- ↑ Ostrom, John H. (1970). "Archaeopteryx: Notice of a "new" specimen". Science 170 (3957): 537–538. doi:10.1126/science.170.3957.537. PMID 17799709.

- ↑ Chambers, Paul (2002). Bones of Contention: The Archaeopteryx Scandals. London: John Murray Ltd. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0719560543.

- ↑ Walker, Alick D. (1972). "New light on the origin of birds and crocodiles". Nature 237 (5353): 257–263. doi:10.1038/237257a0.

- ↑ Ostrom, John H. (1973). "The ancestry of birds". Nature 242 (5393): 136. doi:10.1038/242136a0.

- ↑ Ostrom, John H. (1975). "The origin of birds". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 3: 55–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.03.050175.000415. ISBN 0912532572.

- ↑ Ostrom, John H. (1976). "Archaeopteryx and the origin of birds". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 8 (2): 91–182. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1976.tb00244.x.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T. (1972). "Anatomical and ecological evidence of endothermy in dinosaurs". Nature 238 (5359): 81–85. doi:10.1038/238081a0.

- ↑ Horner, John R.; & Makela, Robert (1979). "Nest of juveniles provides evidence of family structure among dinosaurs". Nature 282 (5736): 296–298. doi:10.1038/282296a0.

- ↑ Hennig, E.H. Willi (1966). Phylogenetic Systematics. translated by Davis, D. Dwight; & Zangerl, Rainer.. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252068149.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Gauthier, Jacques. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". In Padian, Kevin. (ed.). The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences 8. pp. 1–55.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Senter, Phil (2007). "A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5 (4): 429–463. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002143.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Turner, Alan H.; Hwang, Sunny; & Norell, Mark A. (2007). "A small derived theropod from Öösh, Early Cretaceous, Baykhangor, Mongolia". American Museum Novitates 3557 (3557): 1–27. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2007)3557[1:ASDTFS]2.0.CO;2. http://hdl.handle.net/2246/5845.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C.; & Rao Chenggang (1992). "Early evolution of avian flight and perching: new evidence from the Lower Cretaceous of China". Science 255 (5046): 845–848. doi:10.1126/science.255.5046.845. PMID 17756432.

- ↑ Hou Lian-Hai, Lian-hai; Zhou Zhonghe; Martin, Larry D.; & Feduccia, Alan (1995). "A beaked bird from the Jurassic of China". Nature 377 (6550): 616–618. doi:10.1038/377616a0.

- ↑ Ji Qiang; & Ji Shu-an (1996). "On the discovery of the earliest bird fossil in China and the origin of birds". Chinese Geology 233: 30–33.

- ↑ Chen Pei-ji, Pei-ji; Dong Zhiming; & Zhen Shuo-nan. (1998). "An exceptionally preserved theropod dinosaur from the Yixian Formation of China". Nature 391 (6663): 147–152. doi:10.1038/34356.

- ↑ Lingham-Soliar, Theagarten; Feduccia, Alan; & Wang Xiaolin. (2007). "A new Chinese specimen indicates that ‘protofeathers’ in the Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Sinosauropteryx are degraded collagen fibres". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274 (1620): 1823–1829. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0352. PMID 17521978.

- ↑ Ji Qiang, Philip J.; Currie, Philip J.; Norell, Mark A.; & Ji Shu-an. (1998). "Two feathered dinosaurs from northeastern China". Nature 393 (6687): 753–761. doi:10.1038/31635.

- ↑ Sloan, Christopher P. (1999). "Feathers for T. rex?". National Geographic 196 (5): 98–107.

- ↑ Monastersky, Richard (2000). "All mixed up over birds and dinosaurs". Science News 157 (3): 38. doi:10.2307/4012298. http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/94/title/All_mixed_up_over_birds_and_dinosaurs.

- ↑ Xu Xing, Xing; Tang Zhi-lu; & Wang Xiaolin. (1999). "A therizinosaurid dinosaur with integumentary structures from China". Nature 399 (6734): 350–354. doi:10.1038/20670.

- ↑ Xu Xing, X; Norell, Mark A.; Kuang Xuewen; Wang Xiaolin; Zhao Qi; & Jia Chengkai. (2004). "Basal tyrannosauroids from China and evidence for protofeathers in tyrannosauroids". Nature 431 (7009): 680–684. doi:10.1038/nature02855. PMID 15470426.

- ↑ Xu Xing, X; Zhou Zhonghe; Wang Xiaolin; Kuang Xuewen; Zhang Fucheng; & Du Xiangke (2003). "Four-winged dinosaurs from China". Nature 421 (6921): 335–340. doi:10.1038/nature01342. PMID 12540892.

- ↑ Zhou Zhonghe, Z; & Zhang Fucheng (2002). "A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the Early Cretaceous of China". Nature 418 (6896): 405–409. doi:10.1038/nature00930. PMID 12140555.

- ↑ Martin, Larry D. (2006). "A basal archosaurian origin for birds". Acta Zoologica Sinica 50 (6): 977–990.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Feduccia, Alan; Lingham-Soliar, Theagarten; & Hincliffe, J. Richard. (2005). "Do feathered dinosaurs exist? Testing the hypothesis on neontological and paleontological evidence". Journal of Morphology 266 (2): 125–166. doi:10.1002/jmor.10382. PMID 16217748.

- ↑ Burke, Ann C.; & Feduccia, Alan. (1997). "Developmental patterns and the identification of homologies in the avian hand". Science 278 (5338): 666–668. doi:10.1126/science.278.5338.666.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C. (1997). "The origin and evolution of dinosaurs". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 25: 435–489. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.25.1.435.

- ↑ Chiappe, Luis M. (1997). "Aves". In Currie, Philip J.; & Padian, Kevin. (eds.).. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 45–50. ISBN 0-12-226810-5.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Holtz, Thomas R.; & Osmólska, Halszka. (2004). "Saurischia". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; & Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Turner, Alan H.; Pol, Diego; Clarke, Julia A.; Erickson, Gregory M.; & Norell, Mark A. (2007). "A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight". Science 317 (5843): 1378–1381. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350.

- ↑ Osmólska, Halszka; Maryańska, Teresa; & Wolsan, Mieczysław. (2002). "Avialan status for Oviraptorosauria". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 47 (1): 97–116. http://app.pan.pl/article/item/app47-097.html.

- ↑ Martinelli, Agustín G.; & Vera, Ezequiel I. (2007). "Achillesaurus manazzonei, a new alvarezsaurid theropod (Dinosauria) from the Late Cretaceous Bajo de la Carpa Formation, Río Negro Province, Argentina". Zootaxa 1582: 1–17. http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2007f/z01582p017f.pdf.

- ↑ Novas, Fernando E.; & Pol, Diego. (2002). "Alvarezsaurid relationships reconsidered". In Chiappe, Luis M.; & Witmer, Lawrence M. (eds.). Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 0-520-20094-2.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C. (1999). "The evolution of dinosaurs". Science 284 (5423): 2137–2147. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2137. PMID 10381873.

- ↑ Perle, Altangerel; Norell, Mark A.; Chiappe, Luis M.; & Clark, James M. (1993). "Flightless bird from the Cretaceous of Mongolia". Science 362 (6421): 623–626. doi:10.1038/362623a0.

- ↑ Chiappe, Luis M.; Norell, Mark A.; & Clark, James M. (2002). "The Cretaceous, short-armed Alvarezsauridae: Mononykus and its kin". In Chiappe, Luis M.; & Witmer, Lawrence M. (eds.). Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 87–119. ISBN 0-520-20094-2.

- ↑ Forster, Catherine A.; Sampson, Scott D.; Chiappe, Luis M.; & Krause, David W. (1998). "The theropod ancestry of birds: new evidence from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Science 279 (5358): 1915–1919. doi:10.1126/science.279.5358.1915. PMID 9506938.

- ↑ Makovicky, Peter J.; Apesteguía, Sebastián; & Agnolín, Federico L. (2005). "The earliest dromaeosaurid theropod from South America". Nature 437 (7061): 1007–1011. doi:10.1038/nature03996. PMID 16222297.

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. (2002). Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 472pp. ISBN 978-0801867637.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Mayr, Gerald; Pohl, Burkhard; & Peters, D. Stefan (2005). "A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features.". Science 310 (5753): 1483–1486. doi:10.1126/science.1120331. PMID 16322455.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Immoor (9 September 2005). "The Dinosaurs of the Jurassic Park Movies". Geolor.com. http://www.geolor.com/Jurassic_Park_Movies-Fact_versus_Fiction.htm. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ Wellnhofer, P. (1988). Ein neuer Exemplar von Archaeopteryx. Archaeopteryx 6:1–30.

- ↑ Xu, et al. "Basal tyrannosauroids from China and evidence for protofeathers in tyrannosauroids." Nature. 7 October 2004; 431(7009):680-4. PMID: 15470426

- ↑ O'Connor, P.M. and Claessens, L.P.A.M. (2005). Basic avian pulmonary design and flow-through ventilation in non-avian theropod dinosaurs. Nature 436:253.

- ↑ Paul C. Sereno, Ricardo N. Martinez, Jeffrey A. Wilson, David J. Varricchio, Oscar A. Alcober, Hans C. E. Larsson (2008). "Evidence for Avian Intrathoracic Air Sacs in a New Predatory Dinosaur from Argentina". PLoS ONE 3 (9): e3303. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003303. PMID 18825273. PMC 2553519. http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0003303.

- ↑ Fisher, P. E., Russell, D. A., Stoskopf, M. K., Barrick, R. E., Hammer, M. & Kuzmitz, A. A. (2000). Cardiovascular evidence for an intermediate or higher metabolic rate in an ornithischian dinosaur. Science 288, 503–505.

- ↑ Hillenius, W. J. & Ruben, J. A. (2004). The evolution of endothermy in terrestrial vertebrates: Who? when? why? Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 77, 1019–1042.

- ↑ Dinosaur with a Heart of Stone. T. Rowe, E. F. McBride, P. C. Sereno, D. A. Russell, P. E. Fisher, R. E. Barrick, and M. K. Stoskopf (2001) Science 291, 783

- ↑ Xu, X. and Norell, M.A. (2004). A new troodontid dinosaur from China with avian-like sleeping posture. Nature 431:838-841.See commentary on the article.

- ↑ Schweitzer, M.H.; Wittmeyer, J.L.; and Horner, J.R. (2005). "Gender-specific reproductive tissue in ratites and Tyrannosaurus rex". Science 308 (5727): 1456–1460. doi:10.1126/science.1112158. PMID 15933198.

- ↑ Lee, Andrew H.; and Werning, Sarah (2008). "Sexual maturity in growing dinosaurs does not fit reptilian growth models". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (2): 582–587. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708903105. PMID 18195356.

- ↑ Norell, M. A., Clark, J. M., Dashzeveg, D., Barsbold, T., Chiappe, L. M., Davidson, A. R., McKenna, M. C. and Novacek, M. J. (November 1994). "A theropod dinosaur embryo and the affinities of the Flaming Cliffs Dinosaur eggs" (abstract page). Science 266 (5186): 779–782. doi:10.1126/science.266.5186.779. PMID 17730398. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/266/5186/779.

- ↑ Wings O (2007). "A review of gastrolith function with implications for fossil vertebrates and a revised classification". Palaeontologica Polonica 52 (1): 1–16. http://www.app.pan.pl/article/item/app52-001.html.

- ↑ Dal Sasso, C. and Signore, M. (1998). Exceptional soft-tissue preservation in a theropod dinosaur from Italy. Nature 292:383–387. See commentary on the article

- ↑ Schweitzer, M.H., Wittmeyer, J.L. and Horner, J.R. (2005). Soft-Tissue Vessels and Cellular Preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex. Science 307:1952–1955. Also covers the Reproduction Biology paragraph in the Feathered dinosaurs and the bird connection section. See commentary on the article

- ↑ Wang, H., Yan, Z. and Jin, D. (1997). Reanalysis of published DNA sequence amplified from Cretaceous dinosaur egg fossil. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14:589–591. See commentary on the article.

- ↑ Chang, B.S.W., Jönsson, K., Kazmi, M.A., Donoghue, M.J. and Sakmar, T.P. (2002). Recreating a Functional Ancestral Archosaur Visual Pigment. Molecular Biology and Evolution 19:1483–1489. See commentary on the article.

- ↑ Embery, et al. "Identification of proteinaceous material in the bone of the dinosaur Iguanodon." Connect Tissue Res. 2003; 44 Suppl 1:41-6. PMID: 12952172

- ↑ Schweitzer, et al. "Heme compounds in dinosaur trabecular bone." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 10 Jun 1997; 94(12):6291–6. PMID: 9177210

- ↑ Terres, John K. (1980). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York, NY: Knopf. pp. 398–401. ISBN 0394466519.

- ↑ Poling, J. (1996). "Feathers, scutes and the origin of birds". dinosauria.com. http://www.dinosauria.com/jdp/archie/scutes.htm.

- ↑ Prum, R., and Brush, A.H. (2002). "The evolutionary origin and diversification of feathers" (PDF). The Quarterly Review of Biology 77 (3): 261–295. doi:10.1086/341993. PMID 12365352. http://www.mcorriss.com/Prum_&_Brush_2002.pdf.

- ↑ Mayr, G., B. Pohl & D.S. Peters (2005). "A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features". Science, 310(5753): 1483-1486.

- ↑ Feduccia, A. (1999). The Origin and Evolution of Birds. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300078619. http://yalepress.yale.edu/book.asp?isbn=9780300078619. See also Feduccia, A. (February 1995). "Explosive Evolution in Tertiary Birds and Mammals". Science 267 (5198): 637–638. doi:10.1126/science.267.5198.637. PMID 17745839. http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/~rdmp1c/teaching/L3/tutorials/feduccia/feduccia.html.

- ↑ Feduccia, A. (1993).

- ↑ Cretaceous tracks of a bird with a similar lifestyle have been found - Lockley, M.G., Li, R., Harris, J.D., Matsukawa, M., and Liu, M. (August, 2007). "Earliest zygodactyl bird feet: evidence from Early Cretaceous roadrunner-like tracks". Naturwissenschaften 94 (8): 657. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0239-x. PMID 17387416. http://www.springerlink.com/content/hl850l4128573g33/?p=36f762e67c7a46e493a25f6a7ada455d&pi=0.

- ↑ Burgers, P. and L. M. Chiappe (1999). "The wing of Archaeopteryx as a primary thrust generator". Nature (399): 60–62. http://www.stephenjaygould.org/ctrl/news/file013.html.

- ↑ Cowen, R.. History of Life. Blackwell Science. ISBN 0726602876.

- ↑ Videler, J.J. 2005: Avian Flight. Oxford University. Press, Oxford.

- ↑ Burke, A.C., and Feduccia, A. (1997). "Developmental patterns and the identification of homologies in the avian hand" (abstract page). Science 278 (666 date=1997): 666. doi:10.1126/science.278.5338.666. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/278/5338/666?ijkey=dczDGiBvoF7W6. Summarized at "Embryo Studies Show Dinosaurs Could Not Have Given Rise To Modern Birds". ScienceDaily. October 1997. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1997/10/971027064254.htm.

- ↑ Chatterjee, S. (April 1998). "Counting the Fingers of Birds and Dinosaurs". Science 280 (5362): 355. doi:10.1126/science.280.5362.355a. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/280/5362/355a.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Vargas, A.O., Fallon, J.F. (October 2004). "Birds have dinosaur wings: The molecular evidence" (abstract page). Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 304B (1): 86–90. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21023. PMID 15515040. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/109741948/ABSTRACT?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0.

- ↑ There is a video clip of a very young chick doing this at "Wing assisted incline running and evolution of flight". http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=MNxt_-f9dmw&feature=related.

- ↑ Dial, K.P. (2003). "Wing-Assisted Incline Running and the Evolution of Flight" (abstract page). Science 299 (5605): 402–404. doi:10.1126/science.1078237. PMID 12532020. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/299/5605/402. Summarized in Morelle, Rebecca (24 January 2008). "Secrets of bird flight revealed" (Web). Scientists believe they could be a step closer to solving the mystery of how the first birds took to the air.. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7205086.stm. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ↑ Bundle, M.W and Dial, K.P. (2003). "Mechanics of wing-assisted incline running (WAIR)" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology 206 (Pt 24): 4553–4564. doi:10.1242/jeb.00673. PMID 14610039. http://dbs.umt.edu/flightlab/pdf/bundle%20and%20dial%20JEB%202003.pdf.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Senter, P. (2006). "Scapular orientation in theropods and basal birds, and the origin of flapping flight". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (2): 305–313. http://www.app.pan.pl/article/item/app51-305.html.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Sankar, Templin, R.J. (2004) "Feathered coelurosaurs from China: new light on the arboreal origin of avian flight" pp. 251-281. In Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds (P. J. Currie, E. B. Koppelhus, M. A. Shugar, and J. L. Wright (eds.). Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- ↑ Samuel F. Tarsitano, Anthony P. Russell, Francis Horne1, Christopher Plummer and Karen Millerchip (2000) On the Evolution of Feathers from an Aerodynamic and Constructional View Point" American Zoologist 2000 40(4):676-686; doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.676© 2000 by The Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology

- ↑ Hu, D.; Hou, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X. (2009). "A pre-Archaeopteryx troodontid theropod from China with long feathers on the metatarsus". Nature 461 (7264): 640–643. doi:10.1038/nature08322. PMID 19794491.

- ↑ Hopson, James A. "Ecomorphology of avian and nonavian theropod phalangeal proportions:Implications for the arboreal versus terrestrial origin of bird flight" (2001) From New Perspectives on the Origin and Early Evolution of Birds: Proceedings of the International Symposium in Honor of John H. Ostrom. J. Gauthier and L. F. Gall, eds. New Haven: Peabody Mus. Nat. Hist., Yale Univ. ISBN 0-912532-57-2.© 2001 Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University. All rights reserved.

- ↑ Glen, C.L., and Bennett, M.B. (November 2007). "Foraging modes of Mesozoic birds and non-avian theropods" (abstract page). Current Biology 17. http://www.current-biology.com/content/article/abstract?uid=PIIS0960982207019859.

- ↑ Alonso, P.D., Milner, A.C., Ketcham, R.A., Cokson, M.J and Rowe, T.B. (August 2004). "The avian nature of the brain and inner ear of Archaeopteryx". Nature 430 (7000): 666–669. doi:10.1038/nature02706. PMID 15295597. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v430/n7000/full/nature02706.html.

- ↑ Chiappe, L.M.. Glorified Dinosaurs: The Origin and Early Evolution of Birds. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 0471247235.

- ↑ Zhang, F., Zhou, Z., Xu, X. & Wang, X. (2002). "A juvenile coelurosaurian theropod from China indicates arboreal habits". Naturwissenschaften 89 (9): 394–398. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0353-8. PMID 12435090.

- ↑ Chatterjee, S., and Templin, R.J. (2007). "Biplane wing planform and flight performance of the feathered dinosaur Microraptor gui." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(5): 1576-1580. [1]

- ↑ Beebe, C. W. A. (1915). "Tetrapteryx stage in the ancestry of birds." Zoologica, 2: 38-52.

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/details/animalsofpastacc00lucauoft

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (2002). "Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds." Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. page 257

- ↑ Gerald Mayr* and D. Stefan Peters (2006) "Response to Comment on ‘‘A Well-Preserved Archaeopteryx Specimen with Theropod Features’’" www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 313 1 SEPTEMBER 2006 pp. 1238c

- ↑ Ian J. Corfe1, and Richard J. Butler (2006) Comment on ‘‘A Well- Preserved Archaeopteryx Specimen With Theropod Features’’ www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 313 1 SEPTEMBER 2006

- ↑ Scientists Say No Evidence Exists That Therapod Dinosaurs Evolved Into Birds

- ↑ Scientist Says Ostrich Study Confirms Bird "Hands" Unlike Those Of Dinosaurs

- ↑ Embryo Studies Show Dinosaurs Could Not Have Given Rise To Modern Birds

- ↑ 2 Scientists Say New Data Disprove Dinosaur-Bird Theory - New York Times

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Chatterjee, Sankar (17 April 1998). "Counting the Fingers of Birds and Dinosaurs". Science. doi:10.1126/science.280.5362.355a. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/280/5362/355a. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ↑ University of Maryland department of geology home page, "Theropoda I" on Avetheropoda, 14 july 2006.

- ↑ Wagner, G. P. and Gautthier, J. A. 1999. 1,2,3 = 2,3,4: A solution to the problem of the homology of the digits in the avian hand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 5111-5116

- ↑ Scienceblogs: Limusaurus is awesome.

- ↑ Developmental Biology 8e Online. Chapter 16: Did Birds Evolve From the Dinosaurs?

- ↑ Vargas AO, Wagner GP and Gauthier, JA. 2009. Limusaurus and bird digit identity. Available from Nature Precedings [2]

References

- Barsbold, Rinchen (1983): O ptich'ikh chertakh v stroyenii khishchnykh dinozavrov. ["Avian" features in the morphology of predatory dinosaurs]. Transactions of the Joint Soviet Mongolian Paleontological Expedition 24: 96-103. [Original article in Russian.] Translated by W. Robert Welsh, copy provided by Kenneth Carpenter and converted by Matthew Carrano. PDF fulltext

- Bostwick, Kimberly S. (2003): Bird origins and evolution: data accumulates, scientists integrate, and yet the "debate" still rages. Cladistics 19: 369–371. doi:10.1016/S0748-3007(03)00069-0 PDF fulltext

- Dingus, Lowell & Rowe, Timothy (1997): The Mistaken Extinction: Dinosaur Evolution and the Origin of Birds. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York. ISBN 0-7167-2944-X

- Dinosauria On-Line (1995): Archaeopteryx's Relationship With Modern Birds. Retrieved 2006-SEP-30.

- Dinosauria On-Line (1996): Dinosaurian Synapomorphies Found In Archaeopteryx. Retrieved 2006-SEP-30.

- Heilmann, G. (1926): The Origin of Birds. Witherby, London. ISBN 0-486-22784-7 (1972 Dover reprint)

- Mayr, Gerald; Pohl, B. & Peters, D. S. (2005): A Well-Preserved Archaeopteryx Specimen with Theropod Features. Science 310(5753): 1483-1486. doi:10.1126/science.1120331

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985): The fossil record of birds. In: Farner, D.S.; King, J.R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 79-238. Academic Press, New York.

External links

- DinoBuzz A popular-level discussion of the dinosaur-bird hypothesis